By George Beccaloni

"...the main object of all my journeys was to obtain specimens of natural history, both for my private collection and to supply duplicates to museums and amateurs..." (The Malay Archipelago. Wallace, 1869).

EARLY COLLECTIONS (1841 - 1847)

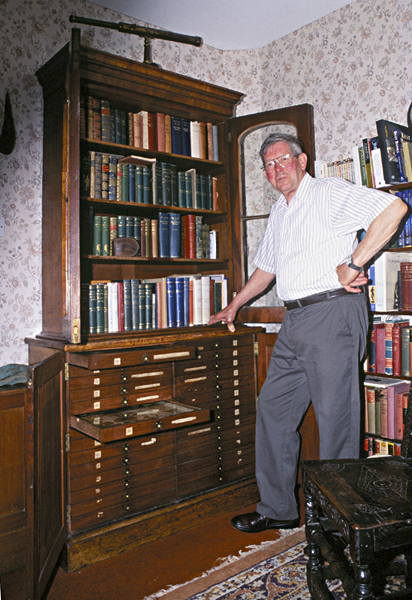

Wallace started to collect natural history specimens, plants in particular, in 1841 whilst he was living near Neath in Wales. He wanted to be able to identify the plants he saw in the countryside whilst doing his land surveying work, so he bought some books on how to identify them and began to form a reference collection of pressed specimens. In 1844 he met and became good friends with amateur entomologist Henry Walter Bates, who soon got Wallace interested in collecting British beetles. Not long afterwards Wallace also started to collect butterflies and moths. In a letter to Bates in 1846 he relates how he bought a 28 drawer cedar and mahogany insect cabinet to house his beetles in. He mentions that he only had glass fitted to 12 of the 28 drawer lids - which gives a good indication of the size of his collection at that time - i.e. fewer specimens than would fill 12 of the drawers. This cabinet is the only one known to have been owned by Wallace (he kept the many specimens he later collected in the tropics in entomological storeboxes) and it is still owned by his descendants. We don't currently know what became of Wallace's early collections (or how the specimens were labelled), although it is likely that he donated them to the Mechanics Institute in Neath (see THIS LETTER and THIS PUBLICATION). They may have ended up in the Swansea Museum, but so far they have not been found. In 1848 Wallace donated two specimens of a beetle (Agonum (near moestum)) from a salt marsh near Swansea to London's Natural History Museum. They should bear a museum label with the accession number "BM 48.33", but unfortunately they can't currently be found.

Before Wallace and Bates left for the Amazon they found an agent in London who would receive the specimens they sent back, keep the ones marked as being for their private collection aside for them, and sell the rest. In his autobiography My Life Wallace says "We were fortunate in finding an excellent and trustworthy agent in Mr. Samuel Stevens,...brother of Mr. J.C. Stevens, the well-known natural history auctioneer, of King Street, Covent Garden. He continued to act as my agent during my whole residence abroad, sparing no pains to dispose of my duplicates to the best advantage, taking charge of my private collections, insuring each collection as its despatch was advised, keeping me supplied with cash, and with such stores as I required, and, above all, writing me fully as to the progress of the sale of each collection, what striking novelties it contained, and giving me general information on the progress of other collectors and on matters of general scientific interest. During the whole period of our business relations, extending over more than fifteen years, I cannot remember that we ever had the least disagreement about any matter whatever."

THE AMAZON (1848 - 1852)

In late 1847 or early 1848 Wallace suggested to Bates that they go to the Amazon to collect specimens of insects, birds and other animals, both for their private collections and to sell to collectors and museums in Europe. Bates liked the idea and the two young men (at the time Wallace was 25 and Bates 23) set off by ship from Liverpool to Pará (now known as Belém) on 26 April 1848. At first they worked as a team, but after a few months they apparently quarrelled and split up to collect in different areas. In Brazil Wallace primarily collected butterflies, birds, and fish. He also collected a few plants, the only ones known to have survived being some palm specimens which are now at Kew Gardens (see below).

By early 1852 Wallace was in poor health and in no condition to continue travelling. He decided to return to England, and began the long trip back down the Rio Negro and Amazon to Pará. Passing through Barra (now known as Manaus), Wallace found to his dismay that most of his specimens from the preceding two years, which he had been sending down river, had been delayed by the officials there because they were worried that the boxes might contain contraband (earlier specimens had already been shipped back to England). After declaring their contents, he collected them and set sail for England on the brig Helen on the 12 July. He had with him ""...a considerable collection of birds, insects, reptiles and fishes, and a large quantity of miscellaneous articles, consisting of about twenty cases and packages."

Tragically, twenty-six days into the voyage, when his ship was in the middle of the Atlantic, it caught fire and sank. Wallace described his loss in a published letter dated 19 October 1852:

"The only things which I saved were my watch, my drawings of fishes, and a portion of my notes and journals. Most of my journals, notes on the habits of animals, and drawings of the transformations of insects, were lost.

My collections were mostly from the country about the sources of the Rio Negro and Orinooko, one of the wildest and least known parts of South America, and their loss is therefore the more to be regretted. I had a fine collection of the river tortoises (Chelydidae) consisting of ten species, many of which I believe were new. Also upwards of a hundred species of the little known fishes of the Rio Negro: of these last, however, and of many additional species, I have saved my drawings and descriptions. My private collection of Lepidoptera contained illustrations of all the species and varieties I had collected at Santarem, Montalegré, Barra, the Upper Amazons, and the Rio Negro: there must have been at least a hundred new and unique species. I had also a number of curious Coleoptera, several species of ants in all their different states, and complete skeletons and skins of an ant-eater and cow-fish, (Manatus); the whole of which, together with a small collection of living monkeys, parrots, macaws, and other birds, are irrecoverably lost.

I may also mention that I had taken same trouble to procure and pack an entire leaf of the magnificent Jupaté palm (Oredoxia regia), fifty feet in length, which I had hoped would form a fine object in the botanical room at the British Museum."

Wallace and the crew struggled to survive in a pair of badly leaking lifeboats, but very luckily, after 10 days drifting on the open sea they were picked up by a passing cargo boat making its way back to Britain. They landed at Deal in England, on the 1st of October 1852. Fortunately, Wallace’s agent Stevens had the foresight to insure his collections for £200. Wallace estimated they had been worth £500, but it was certainly a lot better than nothing.

THE MALAY ARCHIPELAGO (1854 - 1862)

In March 1854 Wallace left Britain on a collecting expedition to the Malay Archipelago (Singapore, Malaysia, Indonesia and East Timor). He spent nearly eight years in the region, and undertook sixty or seventy separate journeys, often in small native boats and canoes, resulting in a combined total of around 14,000 miles of travel. He visited every major island in the archipelago at least once, and several on multiple occasions, and he and his assistants collected almost 110,000 insects, 7,500 shells, 8,050 bird skins, 410 mammal and reptile specimens, and a few ferns. He collected a total of 212 new bird species (naming about half of them himself), so given that around 10,000 bird species are known, this means that he was responsible for discovering about 2% of the entire World bird fauna.

Wallace probably collected specimens of a total of about 5000 new animal (and a few fern) species in the Malay Archipelago. I based this on estimates that he and others who worked on his collections gave e.g. this passage from his book The Malay Archipelago:

"Nearly two thousand of my Coleoptera, and many hundreds of my butterflies, have been already described by various eminent naturalists, British and foreign; but a much larger number remains undescribed. Among those to whom science is most indebted for this laborious work, I must name Mr. F. P. Pascoe, late President of the Entomological Society of London, who has almost completed the classification and description of my large collection of Longicorn beetles (now in his possession), comprising more than a thousand species, of which at least nine hundred were previously undescribed, and new to European cabinets.

The remaining orders of insects, comprising probably more than two thousand species, are in the collection of Mr. William Wilson Saunders, who has caused the larger portion of them to be described by good entomologists. The Hymenoptera alone amounted to more than nine hundred species, among which were two hundred and eighty different kinds of ants, of which two hundred were new."

Wallace kept about 18% of the specimens that he and his assistants collected for his private collection, which by the end of the trip amounted to 3,000 bird skins of about a 1,000 species, at least 20,000 beetles and butterflies of about 7,000 species, plus some vertebrates and land-shells. When he returned to England he used these to gain insights into evolutionary and biogeographic processes, and published 21 scientific articles in which he named and described 295 new species: 120 butterflies, 70 beetles and 105 birds. At least 4,700 other new species were described in about 350 additional publications by leading amateur and professional naturalists based on specimens from ARW's private collection and the "duplicates" his agent Samuel Stevens had sold to museums and private collectors. About 250 of these new species were named after him, usually as wallacii or wallacei.

Wallace's best known zoological discoveries from the trip are perhaps Rajah Brooke's Birdwing Butterfly (Trogonoptera brookiana) from Borneo, Wallace's Golden Birdwing Butterfly (Ornithoptera croesus) from Bacan Island, Indonesia and Wallace's Standard-Wing Bird of Paradise (Semioptera wallacei) from the same island. He also discovered the world's first gliding frog (Wallace's Flying Frog, Rhacophorus nigropalmatus) in Borneo, and the world's largest bee (Wallace's Giant Bee, Chalicodoma pluto), on Bacan Island.

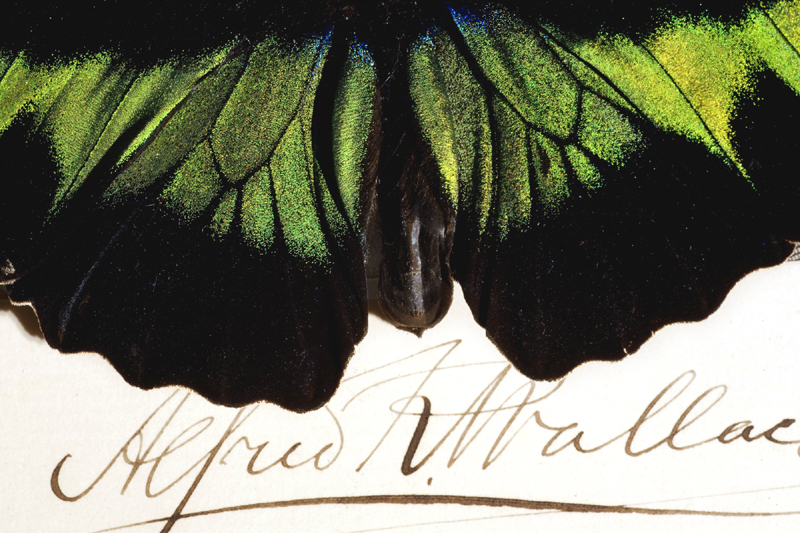

WALLACE'S SPECIMEN LABELS

Wallace was unusual for his time in that he put a locality label on every specimen he collected. Many of his contemporaries, including Bates, were not as meticulous at recording such information. His field labels are very distinctive and enable his specimens to be identified if they are present. Unfortunately the owners of his specimens sometimes took his labels off or replaced them with ones of their own, and if they didn't note the name of the collector (which they sometimes didn't) it may not be possible to determine whether they were collected by Wallace.

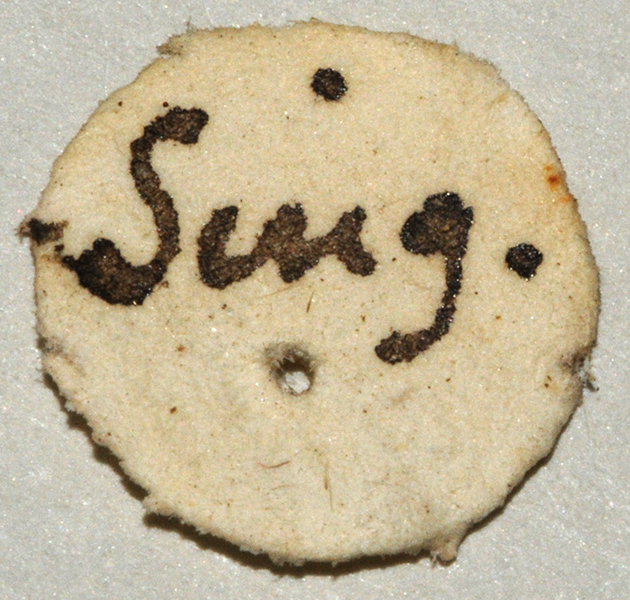

All of his insect specimens were labelled by him (or sometimes by Charles Allen, when he was employed by Wallace), soon after they were collected with a circular c. 8mm disk of usually white, sometimes pale blue, paper with the locality such as the name of an island, written on it in ink. The locality names are often abbreviated e.g. "Sing." for Singapore - see example to the right. We don't know when he started labelling his specimens in this way as none of his pre-Amazon specimens are currently known, but certainly his Amazon and Malay Archipelago insects have such labels.

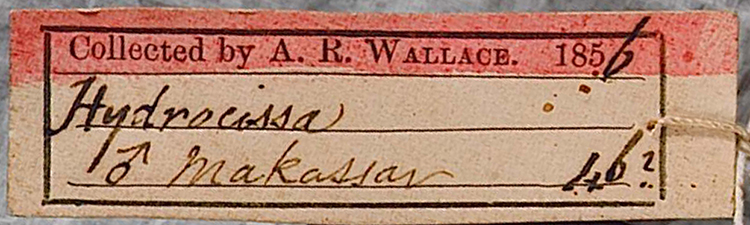

Wallace labelled his vertebrate specimens in the Malay Archipelago with pre-printed labels with the printed text "Collected by A. R. Wallace" (such as the one below) or "Collected for A. R. Wallace". These had a printed year - either "185_" or "186_". Wallace wrote the scientific name of the animal, its sex and the locality on the label in pen. Note that the red top of the label below signifies that it was from a specimen in Wallace's private collection. As he stated in an 1856 letter to Stevens "...all which have a red stripe on the tickets, are private."

Sometimes the label has a number - which refers to an entry in one of his Specimen Register notebooks. These documents are important as they often provide more information about where a specimen was collected etc. Three such notebooks and one separate list survive and they are as follows:

Notebook with lists of birds and beetles collected in Singapore & Malacca in 1854. CLICK HERE to see it.

Notebook with lists of insects, birds and other animals collected from 1855-60. CLICK HERE to see it (page slow to load)

Notebook with lists of insects and birds specimens collected from 1858-66. CLICK HERE to see it (page slow to load).

A list of weevil (beetle) specimens collected in various localities. CLICK HERE to see it.

FATE OF WALLACE'S COLLECTIONS

Around 1867 Wallace decided to sell his private collection and in his autobiography, My Life (1905), he mentions that he retained "…only a few boxes of duplicates to serve as mementoes". The insects he retained are now in the Natural History Museum, London, where they are kept as a separate collection, while at least some of the bird skins he kept are now in the Dorset County Museum.

A good overview of what specimens Wallace collected in the Malay Archipelago can be found in the following paper by the late Donald Baker - CLICK HERE to download a pdf. A paper by Fagan which discusses Wallace as a collector can be downloaded HERE. Images of some of his specimens can be seen HERE.

INSTITUTIONS WITH WALLACE SPECIMENS

UK

Booth Museum of Natural History, Brighton: A few butterfly specimens.

Cambridge University Herbarium: Fern specimens from Sarawak.

Dorset County Museum: c. 46 bird specimens from the Malay Archipelago and other places (1 from Para). These were part of Wallace's private collection and were acquired by Mr Parkinson Curtis from Wallace's widow after his death. They were left to the Museum in Parkinson Curtis's Will.

English Heritage, Down house: One female specimen of the long-armed chafer Euchirus longimanus in a storebox of Darwin's beetles which is on public display. This specimen was sent to Darwin by Wallace. Wallace wrote to Darwin on September 14th 1868 [?] "I send you by post a pair of the Euchirus longimanus. They are not quite perfect and are very rotten from being kept so long in open boxes but will perhaps answer your purpose." He went on to describe the sounds made by this species "Euchirus longimanus. (Amboyna, Ceram) when in motion makes a low hissing sound caused by protrusion and contraction of the abdomen. When seized it also produces a grating sound by rubbing the hind tibiae against the edges of the elytra." (CLICK HERE to see the letter). Darwin mentioned the stridulation in his book The Descent of Man.

Horniman Museum, London: Insect specimens.

Hunterian Museum, Glasgow: Beetle specimens. CLICK HERE for an example.

Linnean Society, London: Skin of a python. This was donated to the Society by Wallace's grandson John in 1958. It is reputed to be the skin of the snake which Wallace found in the roof of his hut on Amboyna (Ambon Island, Indonesia). In The Malay Archipelago he says "It was about twelve feet long and very thick, capable of doing much mischief and of swallowing a dog or a child."

Manchester Museum: A few birds. Unidentified Chrysomelidae beetles.

Natural History Museum, London: A huge selection of all of the groups of organisms he collected, including butterflies and birds from the Amazon, and insects, shells, amphibians, reptiles, birds, mammals and one or more ferns from the Malay Archipelago. A paper mentioning his bird specimens in the NHM can be seen HERE. Also see THIS. There are thought to be about 4,000 bird skins.

National Museum of Wales: c. 50 beetles, one butterfly and 5 bird skins.

Oxford University Museum of Natural History: Numerous insect specimens. An overview of these can be found listed HERE. Also 6 bird skins.

Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew: Palm specimens from the Amazon. Also CLICK HERE.

Sunderland Museum: There are reputed to be Wallace specimens in the collection of exotic butterflies formed by Edward Backhouse (1808-1879).

University Museum of Zoology, Cambridge: Some insects and quite a large number of bird specimens. Amongst these are five of Wallace's skins of Birds of Paradise were sold to the museum by Wallace's son William.

University of Reading, Reading: There are fern specimens from Wallace in the fern collection of Katherine Murray Lyell.

World Museum, Liverpool: Orangutan specimens from Sarawak: one folded skin and skull of a male, and one other skull of a now lost mounted specimen. These were from Lord Derby's collection. He purchased five skins and skulls and two skeletons of orangutans that Wallace collected in Sarawak.

France

Paris Museum: Probably quite a lot of material.

Germany

Museum für Naturkunde, Berlin: Cicindelinae (tiger beetles) ex. the Hermann Schaum collection. Probably a lot of other material too.

The Netherlands

Naturalis, Leiden: 89 bird specimens (including type specimens) from the Malay Archipelago. See http://www.repository.naturalis.nl/document/44313

USA

American Museum of Natural History, New York: 35 bird skins.

California Academy of Sciences: c. 11 beetles from the Malay Archipelago ex. the Edwin C. Van Dyke collection.

Field Museum, Chicago: bird skins. These originated from the AMNH and Princeton Museum. Also see http://youtu.be/KJdHjrkftOQ

Museum of Comparative Zoology, Harvard: A few Chrysomelidae beetles in the Bowditch Collection, plus 4 birds and 1 shell.

Smithsonian, National Museum of Natural History: Two bird skins from the Malay Archipelago are listed in their database.

Princeton Museum: Bird skins.

Australia

Macleay Museum, University of Sydney:

Museum Victoria, Melbourne: 192 birds (purchased from John Gould), 2 bats, 4 mammals plus numerous insects. An example of one of the birds can be SEEN HERE.

South Australian Museum, Adelaide:

Western Australian Museum, Perth: About 400 Hemiptera (true bugs) from the Malay Archipelago in the Francis Buchanan White Collection.

Singapore

Lee Kong Chian Natural History Museum (formerly Raffles Museum): One bird specimen - a flycatcher.

Malaysia: Sarawak

Sarawak Museum, Kuching: In 2013 Darren Mann (Oxford University Museum, UK) presented this museum with a dung beetle specimen which Wallace collected in Sarawak. This is the only Wallace insect specimen in South-East Asia.

Japan

The Yamashina Institute for Ornithology, Tokyo: two of Wallace's bird skins, one of the Morotai friarbird Philemon fuscicapillus (Y10.50381) and the other of the Rusty pitohui Pitohui fuscicapillus

(Y10.39588).

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Very many thanks to the following kind people for useful information: Kate Hebditch (Dorset County Museum); Norm Penny (CAS); Rolf Schmidt (Museum Victoria); Fred Edwards (UK); Julian Carter (National Museum of Wales); Bernd Jaeger (Museum für Naturkunde).

REFERENCES