Wallace spent 8 years travelling and collecting natural history specimens (mainly beetles, butterflies and birds) in the Malay Archipelago (now Singapore, Malaysia and Indonesia) - an experience he regarded as being the defining period of his life. He left England in March 1854 when he was 31 years of age and arrived back in April 1862, when he was 39. The sculpture the WMF hopes to commission to commemorate the 100th anniversary of Wallace's death in 2013 will depict him as he was during this time.

What did Wallace look like aged 31 – 39?

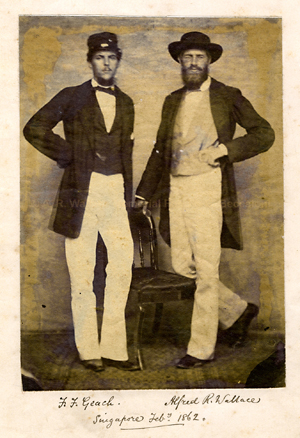

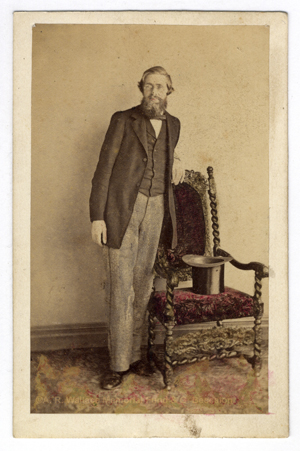

Unfortunately there is only a single known photograph of Wallace taken between March 1854 and April 1862, when he was out in the ‘Malay Archipelago’ (right). He was photographed in Singapore in February 1862, shortly before his long voyage back to England, along with his close friend, the mining engineer Frederick Geach. Curiously Marchant’s 1916 book Alfred Russel Wallace; Letters and Reminiscences includes a ‘doctored’ version of this image, with Geach neatly painted out!

Unfortunately there is only a single known photograph of Wallace taken between March 1854 and April 1862, when he was out in the ‘Malay Archipelago’ (right). He was photographed in Singapore in February 1862, shortly before his long voyage back to England, along with his close friend, the mining engineer Frederick Geach. Curiously Marchant’s 1916 book Alfred Russel Wallace; Letters and Reminiscences includes a ‘doctored’ version of this image, with Geach neatly painted out!

See https://picasaweb.google.com/WallaceMemorialFund/ImagesOfAlfredRusselWallace# for (nearly!) all known images of Wallace.

Wallace's attire in the field

No detailed description of the clothes Wallace wore whilst doing fieldwork is present in his writings, but the outfit he was wearing in the famous photo of himself and Geach in Singapore is almost certainly not what he wore whilst out collecting. In a 1854 letter he mentions the "English preserve the tight fitting coat, waistcoat, and trousers, and the abominable hat and cravat" which is exactly what he is wearing in this photo. The reason he was dressed like this was because he was in a big city, not out collecting specimens.

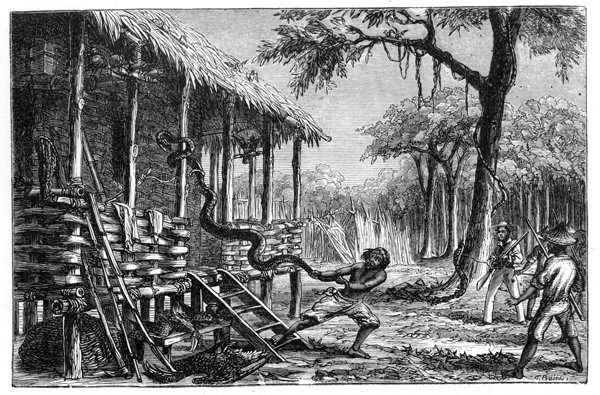

Interestingly, Wallace is depicted in two woodcut illustrations in his book The Malay Archipelago. The woodcut showing him most clearly is “Ejecting an intruder” (right). His clothing is likely to be accurately portrayed in this picture, as it was based on a sketch he drew. Unfortunately, however, he is so small that the details of his outfit are difficult to make out (below). It looks like he is wearing an open necked shirt (minus cravat), a wide-brimmed hat and white trousers.

Interestingly, Wallace is depicted in two woodcut illustrations in his book The Malay Archipelago. The woodcut showing him most clearly is “Ejecting an intruder” (right). His clothing is likely to be accurately portrayed in this picture, as it was based on a sketch he drew. Unfortunately, however, he is so small that the details of his outfit are difficult to make out (below). It looks like he is wearing an open necked shirt (minus cravat), a wide-brimmed hat and white trousers.

In the text cited below he mentions that he wore a “hunting-shirt” whilst collecting. This is a shirt with at least two pockets – but it is unclear where these would have been positioned and also whether the shirt had buttons. It is probable that he didn’t have his shirt sleeves rolled up, as it is clear from the following passage from The Malay Archipelago that the natives in Sarawak hadn’t seen the colour of the skin of his arms even though he was staying in their village: “Many of the women and children had never seen a white man before, and were very sceptical as to my being the same colour all over, as my face. They begged me to show them my arms and body, and they were so kind and good-tempered that I felt bound to give them some satisfaction, so I turned up my trousers and let them see the colour of my leg, which they examined with great interest.” This is not a surprise since sleeves would have protected his arms from the sun, thorns and insect bites.

In a letter from Sarawak in 1855 he describes the collecting equipment he carried with him whilst out hunting insects:

"To give English entomologists some idea of the collecting here, I will give a sketch of one good day's work. Till breakfast I am occupied ticketing and noting the captures of the previous day, examining boxes for ants, putting out drying-boxes and setting the insects of any caught by lamp-light. About 10 o'clock I am ready to start. My equipment is, a rug-net [this is probably a misprint for “bag-net”1, which was what he called his net elsewhere], large collecting-box hung by a strap over my shoulder, a pair of pliers [wide, flat tweezers] for Hymenoptera [ants, bees & wasps], two bottles with spirits, one large and wide-mouthed for average Coleoptera [beetles], &c., the other very small for minute and active insects, which are often lost by attempting to drop them into a large mouthed bottle. These bottles are carried in pockets in my hunting-shirt, and are attached by strings round my neck; the corks are each secured to the bottle by a short string."

Wallace would have carried his net, ready for use, in his right hand, since he was right handed. The “large collecting-box”2 he refers to above was a cork-lined box, into which he pinned butterflies and other delicate winged insects after he caught and killed them. We know this from the following passage from The Malay Archipelago: “One day when in the forest an old man stopped to look at me catching an insect. He stood very quiet till I had captured pinned and put it in my collecting box when he could contain himself no longer, but bent himself almost double & enjoyed a hearty roar of laughter.” In Tropical Nature, and Other Essays he mentions having a “…large tin collecting box full of rare butterflies and other insects…”. Wallace's collecting box was probably made of tin and Japanned black, and the cork sheet in its base would have been kept damp to prevent the insects from drying out, thus allowing them to be set when Wallace returned home. Wallace mentions that the collecting box he had was “large”. In a letter many years later to his daughter Violet he said "I have found one small collecting box. Is it any use to you now? It is about 5 inches x 3 inches.", so it was probably larger than this. Greene in his 1863 book The Insect Hunter’s Companion (p. 64) describes a collecting box 9 x 6 x 1.75 inches, and an 1890 advert from a dealer in entomological equipment lists one of 9 x 7 inches. Given the large size of many tropical butterflies it is likely that Wallace’s collecting box was this size or larger. In an article in 1891 in Entomological news and proceedings of the Entomological Section of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia (p. 63) it says that the collecting box was hung "...by a strap over the shoulder, and a little in front of the body on the left side, this will give the collector ample play with both arms and hands."

Wallace would have carried his net, ready for use, in his right hand, since he was right handed. The “large collecting-box”2 he refers to above was a cork-lined box, into which he pinned butterflies and other delicate winged insects after he caught and killed them. We know this from the following passage from The Malay Archipelago: “One day when in the forest an old man stopped to look at me catching an insect. He stood very quiet till I had captured pinned and put it in my collecting box when he could contain himself no longer, but bent himself almost double & enjoyed a hearty roar of laughter.” In Tropical Nature, and Other Essays he mentions having a “…large tin collecting box full of rare butterflies and other insects…”. Wallace's collecting box was probably made of tin and Japanned black, and the cork sheet in its base would have been kept damp to prevent the insects from drying out, thus allowing them to be set when Wallace returned home. Wallace mentions that the collecting box he had was “large”. In a letter many years later to his daughter Violet he said "I have found one small collecting box. Is it any use to you now? It is about 5 inches x 3 inches.", so it was probably larger than this. Greene in his 1863 book The Insect Hunter’s Companion (p. 64) describes a collecting box 9 x 6 x 1.75 inches, and an 1890 advert from a dealer in entomological equipment lists one of 9 x 7 inches. Given the large size of many tropical butterflies it is likely that Wallace’s collecting box was this size or larger. In an article in 1891 in Entomological news and proceedings of the Entomological Section of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia (p. 63) it says that the collecting box was hung "...by a strap over the shoulder, and a little in front of the body on the left side, this will give the collector ample play with both arms and hands."Endnotes

1. Salmon (2000) in his book The Aurelian Legacy: British Butterflies and Their Collectors says: "The earliest recorded date in the history of the butterfly net is 1711, when Petiver visited Holland and returned with the first known 'muscipula' or bag-net. This was a ring-net: a hoop attached to a stick on which a bag of muslin netting was suspended."