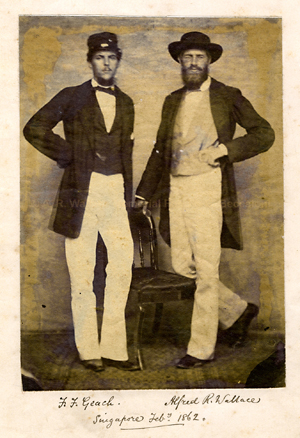

What did Wallace look

like aged 31 – 39? Unfortunately there is only a single known photograph of

Unfortunately there is only a single known photograph of

Wallace taken between March 1854 and April 1862, when he was out in the ‘Malay

Archipelago’ (right). He was photographed in Singapore in February 1862, shortly before

his long voyage back to England, along with his close friend, the mining

engineer Frederick Geach. Curiously Marchant’s 1916 book Alfred Russel Wallace; Letters and Reminiscences includes a

‘doctored’ version of this image, with Geach neatly painted out!

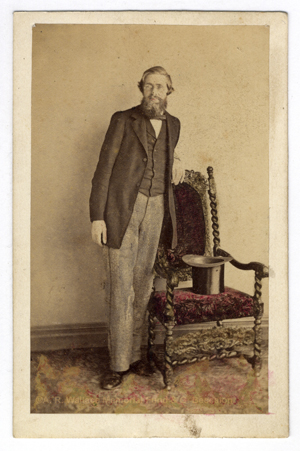

The only other photo of Wallace from this period is one

taken in England by his brother-in-law Thomas Sims shortly after Wallace’s

return from South-east Asia – probably also in 1862 (left). The only surviving

contemporary copy of this image is a hand-coloured print in carte de visite

format which belongs to the Wallace family.

See https://picasaweb.google.com/WallaceMemorialFund/ImagesOfAlfredRusselWallace#

for (nearly!) all known images of Wallace.

Wallace's attire in

the field

No detailed description of the clothes Wallace wore whilst

doing fieldwork is present in his writings, but the outfit he was wearing in

the famous photo of himself and Geach in Singapore is almost certainly not what he wore whilst out collecting.

In a 1854 letter he mentions the "English preserve the tight fitting coat,

waistcoat, and trousers, and the abominable hat and cravat" which is

exactly what he is wearing in this photo. The reason he was dressed like this

was because he was in a big city, not out hunting specimens.

Interestingly, Wallace is depicted in two woodcut

Interestingly, Wallace is depicted in two woodcut

illustrations in his book The Malay

Archipelago. The woodcut showing him most clearly is “Ejecting an intruder” (right).

His clothing is likely to be accurately portrayed in this picture, as it was

based on a sketch he drew. Unfortunately, however, he is so small that the

details of his outfit are difficult to make out (below). It looks like he is wearing an

open necked shirt (minus cravat), a wide-brimmed hat and baggy trousers.

in damp forest at least, Wallace tucked his trousers into his socks to avoid

leaches. He says: “I escaped [leaches] myself, by wearing my worsted socks over

my trousers, and kept in their place by boots laced up over them.” (see http://people.wku.edu/charles.smith/wallace/S019.htm).

He notes in The Malay Archipelago

that he wore waterproof leather boots.

In

the text cited below he mentions that he wore a “hunting-shirt” whilst

collecting. This is a shirt with at least two pockets – but it is unclear where

these would have been positioned and also whether the shirt had buttons. It is

probable that he didn’t have his shirt sleeves rolled up, as it is clear from

the following passage from The Malay

Archipelago that the natives in Sarawak hadn’t seen the colour of the skin

of his arms: “Many of the women and children had never seen a white man before,

and were very sceptical

as to my being the same colour all over, as my face. They begged me to show

them my arms and body, and they were so kind and good-tempered that I felt

bound to give them some satisfaction, so I turned up my trousers and let them

see the colour of my leg, which they examined with great interest.” This is not

a surprise since sleeves would have protected his arms from the sun, thorns and

insect bites.

In a letter from Sarawak in

1855 he mentions the collecting equipment he carried with him whilst out

hunting insects:

"To give English entomologists some idea of the

collecting here, I will give a sketch of one good day's work. Till breakfast I

am occupied ticketing and noting the captures of the previous day, examining

boxes for ants, putting out drying-boxes and setting the insects of any caught

by lamp-light. About 10 o'clock I am ready to start. My equipment is, a rug-net

[this is probably a misprint for “bag-net”1, which was what he

called his net elsewhere], large collecting-box hung by a strap over my

shoulder, a pair of pliers [wide, flat tweezers] for Hymenoptera [ants, bees

& wasps], two bottles with spirits, one large and wide-mouthed for average

Coleoptera [beetles], &c., the other very small for minute and active

insects, which are often lost by attempting to drop them into a large mouthed

bottle. These bottles are carried in pockets in my hunting-shirt, and are

attached by strings round my neck; the corks are each secured to the bottle by

a short string."

Wallace would have carried his net, ready for use, in his right

hand, since he was right handed. The “large collecting-box” he refers to above was

a cork-lined tin box, into which he pinned butterflies and other delicate

winged insects after he caught and killed them. We know this from the following

passage from The Malay Archipelago:

“One day when in the forest an old man stopped to look at me catching an

insect. He stood very quiet till I had captured pinned and put it in my

collecting box when he could contain himself no longer, but bent himself almost

double & enjoyed a hearty roar of laughter.” In Tropical Nature, and Other Essays he mentions having a “…large tin

collecting box full of rare butterflies and other insects…”. The collecting box

was probably made of tin and Japanned black, and the cork in it was kept damp

to prevent the insects from drying out. Wallace mentions that the collecting

box he had was “large”. In a letter to his daughter Violet he said "I have found one small collecting

box. Is it any use to you now? It is about 5 inches x 3 inches.",

so it was probably larger than this. Greene in his 1863 book The Insect Hunter’s Companion (p. 64)

describes a collecting box 9 x 6 x 1.75 inches, and an 1890 advert from a

dealer in entomological equipment lists one of 9 x 7 inches. Given the large

size of many tropical butterflies it is likely that Wallace’s collecting box

was this size or larger. In an article in 1891 in Entomological

news and proceedings of the Entomological Section of the Academy of Natural

Sciences of Philadelphia (p. 63) it says that the collecting box was hung "...by

a strap over the shoulder, and a little in front of the body on the left side,

this will give the collector ample play with both arms and hands."

Endnotes

1. Salmon (2000) in his book The

Aurelian Legacy: British Butterflies and Their Collectors says: "The

earliest recorded date in the history of the butterfly net is 1711, when

Petiver visited Holland and returned with the first known 'muscipula' or

bag-net. This was a ring-net: a hoop attached to a stick on which a bag of

muslin netting was suspended."