By George Beccaloni & Charles Smith

(Last updated January 2015)

Click here for a timeline of places and houses where Wallace lived

Kensington Cottage around c. 1900. Copyright: A. R. Wallace Memorial Fund & G. W. Beccaloni

Alfred Russel Wallace was born in Kensington Cottage near Usk, Monmouthshire, England (now part of Wales) on the 8th of January 1823 to Thomas Vere Wallace and Mary Ann Wallace (née Greenell), a downwardly mobile middle-class English couple who had moved there from London a few years earlier in order to reduce their living costs.

Wallace's parents. Copyright Wallace Memorial Fund.

Wallace was the eighth of nine children, three of whom did not survive to adulthood. Wallace's father was of Scottish descent (reputedly, of a line leading back to the famous William Wallace); whilst the Greenells were a respectable Hertford family. His great grandfather on his mother's side was twice Mayor of Hertford (in 1773 and 1779).

In 1828 when Wallace was five, he and his family moved to Hertford and it was there, at Hertford Grammar School, that he received his only formal education. In about 1835 Wallace's father was swindled out of his remaining assets and the family fell on very hard times. Wallace was forced to leave school in March 1837, when he was only 14 and was sent to London to lodge with his older brother John who was a carpenter.

Hertford Grammar School (from a watercolour by Eliza Dobinson c. 1815). Copyright Tom Gladwin.

The interior of the Old Grammar School c. 1900, showing the single long room in which all the

teaching was done. A portrait of the founder, Richard Hale, can be seen above the

door on the left. Copyright Hertfordshire Archives & Local Studies (Photo: Mr Elsden).

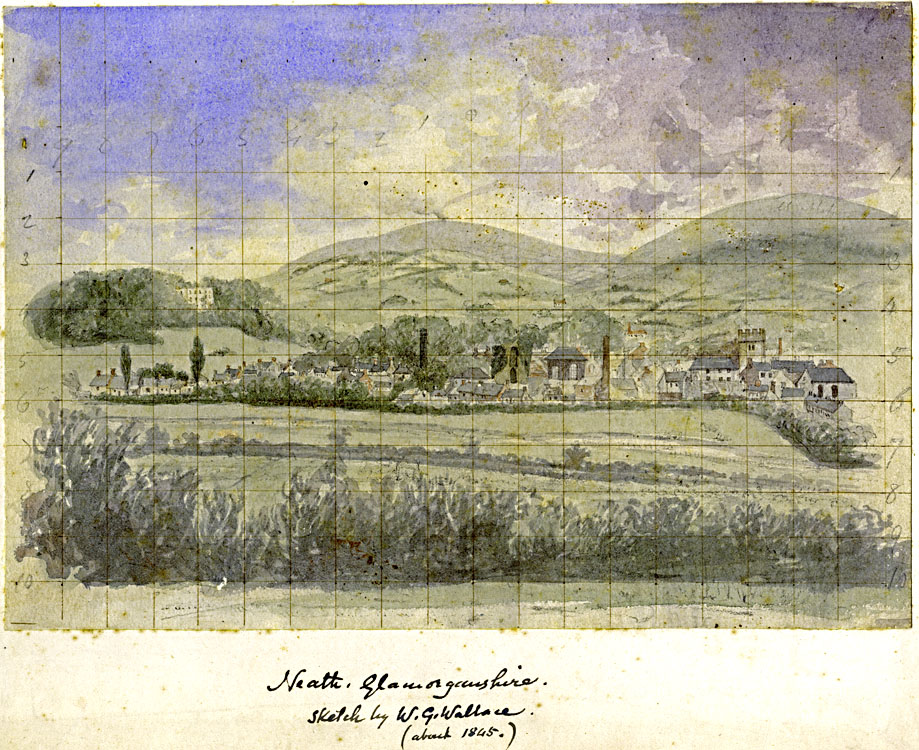

By mid 1837 Alfred had left London to join his eldest brother, William, in Bedfordshire. William owned a land-surveying business, and he was to learn the trade. Wallace and his brother would do such work for the next six and a half years, roaming all over the countryside of southern England and Wales. In the autumn of 1841 the Wallace brothers moved to the Neath area of Wales and it was there that Alfred's interest in natural history really began. It started because he wanted to be able to identify the plants he saw in the countryside while out surveying. He bought his first books on how to identify them and also began to collect them, forming a collection of pressed specimens.

Watercolour painting of Neath, Wales, by Wallace's brother William c. 1845. Copyright Wallace Memorial Fund.

In late 1843 a slump in surveying work forced William to let his brother go. Wallace decided to apply for a position at the Collegiate School in Leicester, and was hired as a master to teach drafting, surveying, English, and arithmetic. Leicester had a good library, and there he was able to find and study several important works on natural history. It was probably in this library that he first met amateur naturalist Henry Walter Bates, who soon got Wallace passionate about collecting and studying beetles. Wallace was amazed by "their many strange forms and often beautiful markings or colouring" and the fact that about a thousand different species could be found within 10 miles of the town.

The Collegiate School in Leicester.

In 1845 Wallace moved back to Neath and it was there that he first read Robert Chambers' anonymously published controversial book Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation, which convinced him of the reality of evolution (then known as transmutation). In late 1847/early 1848 Wallace, inspired by W. H. Edward's book A Voyage Up the River Amazon, suggested to Bates that they travel to Brazil to collect specimens of insects, birds and other animals, both for their private collections and to sell to collectors and museums in Europe. One of the aims of the expedition, at least as far as Wallace was concerned, was to seek evidence for evolution and attempt to discover its mechanism. Bates liked the idea and the two young men (at the time Wallace was 25 and Bates 23) set off by ship from Liverpool to Pará (Belém) on the 26th April 1848, arriving on the 28th May.

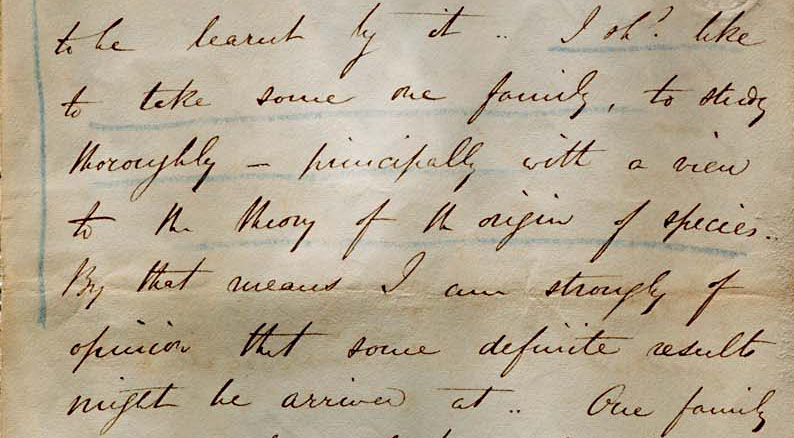

In this 1847 letter to Bates, Wallace mentions his interest in evolution:- "I begin to feel rather dissatisfied

with a mere local collection [of insects] - little is to be learnt by it. I sh[oul]d. like to take some one family,

to study thoroughly - principally with a view to the theory of the origin of species."

Copyright Wallace Literary Estate, The Natural History Museum, Fred Edwards.

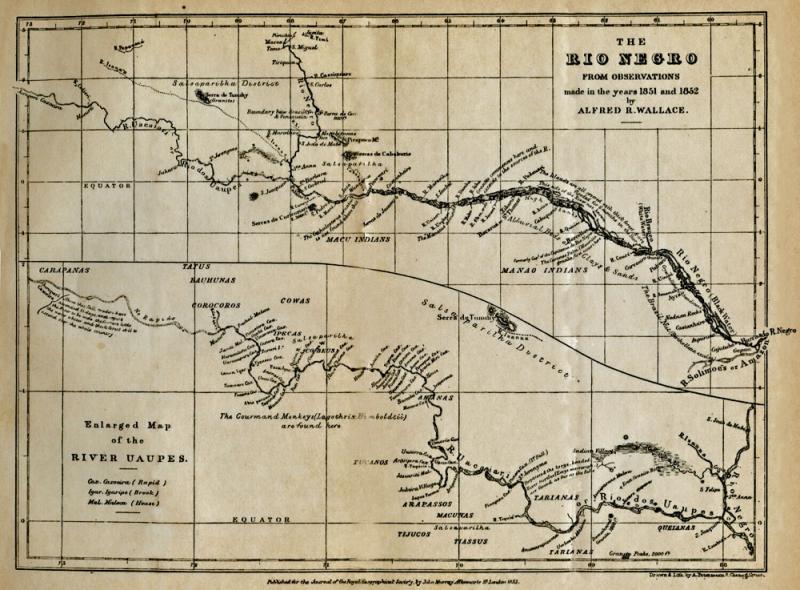

At first they worked as a team, but after a few months they had a disagreement, and split up to collect in different areas. Wallace centered his activities in the middle Amazon and Rio Negro, drafting a map of this mighty river using the skills he had learnt as a land surveyor. Some years later this was published by the Royal Geographical Society, London and it proved accurate enough to become the standard map of the region for many years.

Wallace's map of the Rio Negro river in Brazil published in 1853. Copyright George Beccaloni

In 1852 Wallace was in poor health and decided to return to Britain. However, twenty-six days into the voyage disaster struck: the ship he was on caught fire and sank, taking with it his irreplaceable notes and all the specimens he had collected during the previous two (and most interesting) years.

Illustration from an 1886 book showing Wallace's ship, the Helen, burning.

Wallace and the crew struggled to survive in a pair of badly leaking lifeboats, and fortunately after 10 days drifting in the open sea they were picked up by a passing cargo ship making its way back to England. Luckily, Wallace's agent in London had had the good sense to insure his collections, but unfortunately for less than they were worth.

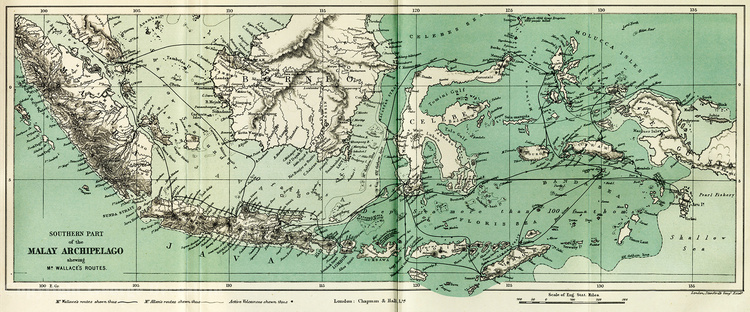

Route of Alfred Russel Wallace's journey (heavy black line) around the Malay Archipelago, from his book 'The Malay Archipelago'.

Copyright George Beccaloni

Wallace was not put off by this unpleasant experience for long, and in 1854 he left Britain again on a collecting expedition to the Malay Archipelago (now Singapore, Malaysia, Indonesia and East Timor). He arrived in Singapore on the 19th April together with a young assistant, Charles Allen. Wallace would spend nearly eight years in the region, undertaking sixty or seventy separate journeys resulting in a combined total of around 14,000 miles of travel. He visited every important island in the archipelago at least once, and several on multiple occasions, and collected almost 110,000 insects, 7500 shells, 8050 bird skins, and 410 mammal and reptile specimens, including probably more than 5000 species new to science. His best known zoological discoveries are Wallace's Golden Birdwing Butterfly (Ornithoptera croesus) and Wallace's Standard-Wing Bird of Paradise (Semioptera wallacei), both from Bacan island, and Rajah Brooke's Birdwing Butterfly (Trogonoptera brookiana) from Borneo. The book he later wrote describing his work and experiences there, The Malay Archipelago, is the most celebrated of all travel writings on this region, and ranks with a few other works as one of the best scientific travel books of the nineteenth century.

Wallace's Golden Birdwing Butterfly (Ornithoptera croesus). Copyright Natural History Museum, London.

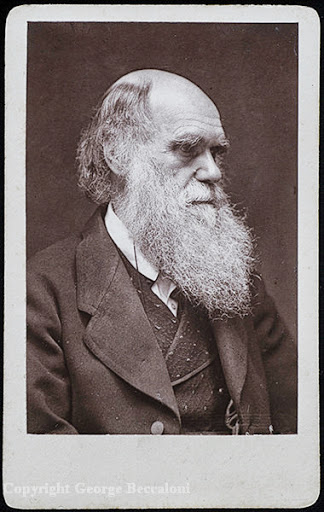

In February 1855 whilst staying in a small house in Sarawak, Borneo, Wallace wrote what was probably the most important paper on evolution prior to the discovery of natural selection. Wallace's "Sarawak Law " paper made such an impression on the famous geologist Charles Lyell that in November 1855, soon after reading it, he started a "species notebook" in which he began to seriously contemplate the implications of evolutionary change. In April 1856 Lyell paid a visit to Charles Darwin at Down House, and Darwin explained his theory of natural selection to Lyell for the first time: a theory which Darwin had been working on, more or less in secret, for about 20 years. Soon afterwards Lyell sent a letter to Darwin urging him to publish the theory lest someone beat him to it (he probably had Wallace in mind!), so in May 1856 Darwin heeding this advice, began to write a "sketch" of his ideas for publication. This "sketch" was abandoned in about October 1856 and Darwin instead began to write an extensive book about evolution.

Charles Darwin in 1874, from a Woodburytype carte de visite published by John G. Murdoch.

Copyright G. W. Beccaloni

In February 1858 Wallace was suffering from an attack of fever (probably malaria) in the village of Dodinga on the remote Indonesian island of Halmahera when suddenly the idea of natural selection as the mechanism of evolutionary change occurred to him. As soon as he had sufficient strength he wrote an detailed essay explaining his theory and sent it together with a covering letter to Charles Darwin, who he knew from correspondence was interested in the subject of evolution. He asked Darwin to pass the essay on to Charles Lyell if Darwin thought it was sufficiently interesting. Lyell (who Wallace had never corresponded with) was one of the most respected scientists of the day and Wallace must have thought that he would be interested in reading his new theory because it explained the "law" which Wallace had proposed in his "Sarawak Law" paper. Darwin had mentioned in a letter to Wallace that Lyell had found Wallace's 1855 paper noteworthy. Another reason why Wallace wanted Lyell to read his essay was because it was written as an argument against the anti-evolutionary views in Lyell's book, Principles of Geology.

Pencil sketch of Ternate Island (left), Tidore Island (middle) and Moti Island (right) (all in the Moluccas, Indonesia) by

Wallace in 18??. Wallace's essay on natural selection was posted from Ternate.

Copyright of scan: A. R. Wallace Memorial Fund.

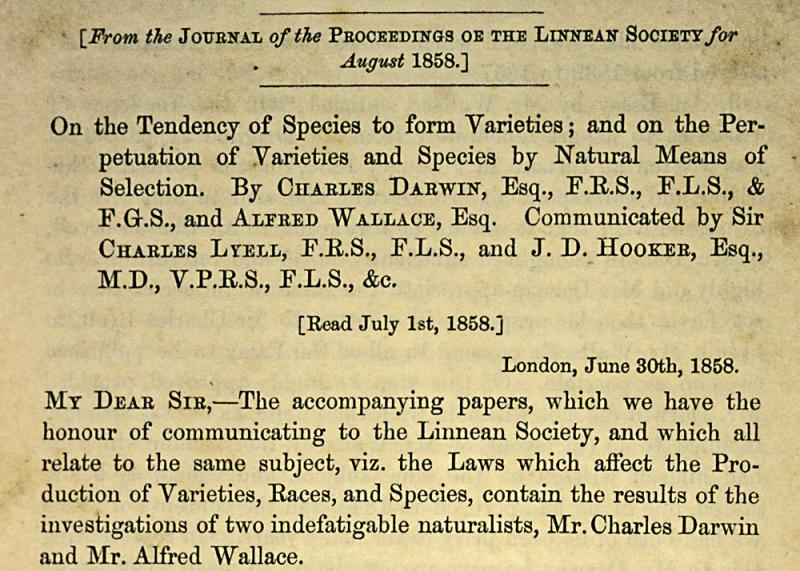

Unbeknownst to Wallace, Darwin had (of course) discovered natural selection many years earlier. He was therefore horrified when he received Wallace's letter and immediately appealed to his influential friends Lyell and Joseph Hooker for advice on what to do. Lyell and Hooker decided to present Wallace's essay (without first asking his permission!), along with two unpublished excerpts from Darwin's writings on the subject, to a meeting of the Linnean Society of London on 1 July 1858. These documents were published together in the Society's journal on 20 August of the same year as the paper "On the Tendency of Species to Form Varieties; And On the Perpetuation of Varieties and Species by Natural Means of Selection". Darwin's contributions were placed before Wallace's essay, thus emphasising Darwin's priority to the idea. Wallace later remarked that the paper "was printed without my knowledge, and of course without any correction of proofs", contradicting Lyell and Hooker's statement in their introduction to the joint papers that "both authors...[have]...unreservedly placed their papers in our hands". This unfortunate event prompted Darwin to abandon writing his big book on evolution and instead produce an "abstract" of what he had written up until that point. This "abstract" was published fifteen months later in November 1859 as his famous book On the Origin of Species.

Darwin & Wallace's 1858 paper on natural selection. Copyright Natural history Museum, London.

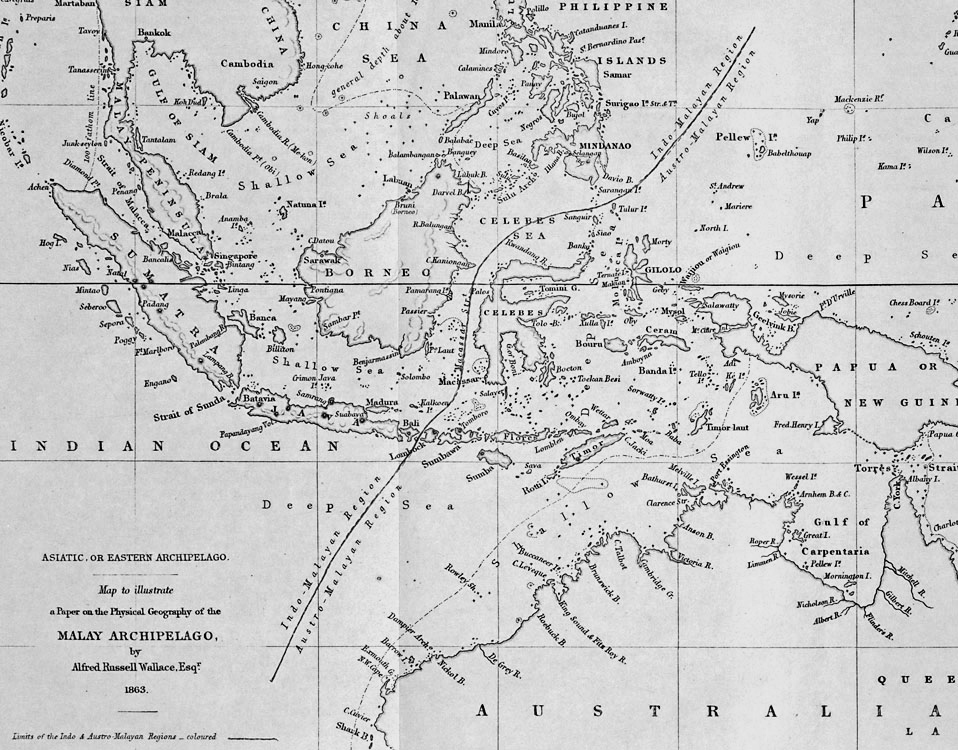

Wallace's discovery of natural selection occurred almost at the midpoint of his stay in the Malay Archipelago. He was to remain there four more years, and by the end of his trip (and for the rest of his life) he was known as the greatest living authority on the region. He was especially known for his studies of its zoogeography, including his discovery and description of the faunal discontinuity that now bears his name. The "Wallace Line," extends between the islands of Bali and Lombok and Borneo and Sulawesi, and marks the limits of eastern extent of many Asian animal species and, conversely, the limits of western extent of many Australasian animals.

Map of the 'Malay Archipelago' showing position of the Wallace Line. Copyright G. W. Beccaloni.

Wallace returned to England in 1862 and in the spring of 1866 he married Annie, the twenty-year-old daughter of his friend the botanist William Mitten. Two of their children, Violet and William, survived to adulthood, whilst a third (Herbert Spencer) died in infancy.

Wallace's wife Annie in c. 1895 from Marchant (1916). Copyright: A. R. Wallace Memorial Fund & G. W. Beccaloni

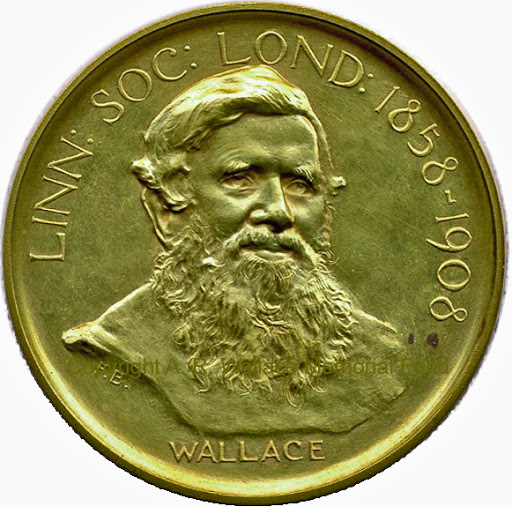

Wallace spent the rest of his long life defending and popularising the theory of natural selection and working on a very wide variety of other subjects. He wrote more than 1000 articles and 22 books, the best known being The Malay Archipelago, The Geographical Distribution of Animals, Island Life and Darwinism. Honours awarded for the many important contributions he made to biology, geography, geology and anthropology include: the Gold Medal (Société de Géographie); the Founder's Medal (Royal Geographical Society); the Darwin-Wallace and Linnean Gold Medals (Linnean Society); the Copley, Darwin and Royal Medals (Royal Society); and the Order of Merit (the greatest honor that can be given to a civilian by the ruling British monarch).

Darwin-Wallace medal of the Linnean Society of London (Wallace side). Copyright A. R. Wallace Memorial Fund.

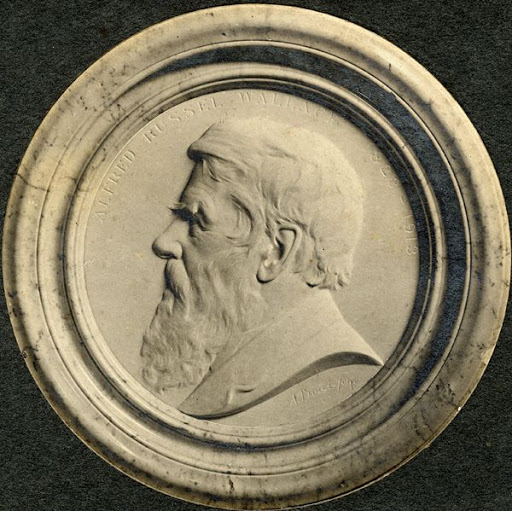

By the turn of the century, Wallace was very probably Britain's best known naturalist and by the end of his life, he may well have been one of the world's most famous people. He remained active into his ninety-first year but slowly weakened in his final months. He died in his sleep at Broadstone on 7 November 1913, and three days later he was buried in a public cemetery nearby. On the 1st November 1915 a medallion bearing his name was placed in Westminster Abbey next to the memorial to Darwin.

Medallion in Westminster Abbey. Copyright Wallace Memorial Fund & George Beccaloni.

Notes

1) For a longer more detailed biography see http://people.wku.edu/charles.smith/wallace/BIOG.htm

2) Although it is commonly believed that Wallace wrote his 1858 essay about natural selection on the Indonesian island of Ternate, his unpublished Field Journal in the Linnean Society shows that he was in fact on the neighboring island of Gilolo (now called Halmahera) in February 1858 when he wrote it. It is probable that he wrote "Ternate" on it simply because this was the island where he had his base and therefore it was his postal address.

3) The 'conspiracy theory' that Darwin stole ideas about species divergence from Wallace's 1858 essay was convincingly debunked by Beddall, B. G. (1988). Darwin and divergence: The Wallace connection. Journal of the History of Biology 21(1): 1-68. Also see http://www.skeptic.com/eskeptic/08-07-02

For a Bahasa Indonesia translation of the above by Made Mahardika see:

http://www.facebook.com/notes/evolusi/sejarah-tentang-wallace/129986043741185

For a Romanian translation by Alexander Ovsov see:

http://webhostinggeeks.com/science/biography-wallace-rm

For a Hungarian tranlation by Szabolcs Csintalan see:

http://www.forallworld.com/eletrajz-wallace/

A Spanish translation by Federico Andres De Maio is available here:

http://alfredrusselwallace-argentina.blogspot.com.ar/2013/07/biografia-de-wallace-por-george.html

A Portuguese translation by Josmael Corso is available here:

http://wallacefund.info/content/biografia-de-wallace

A French translation by Avice Robitaille is available here:

https://worldliterate.com/translations/biography-wallace.html

A German translation by Philip Egger is available here:

https://www.a-writer.org/science/#Biography-of-Wallace:DE